It is worth noting that the number of Jews’ in Transcarpathia until the second half of the 18th century were very small. At this time, a growing number of Jewish fugitives began to arrive in the North-Eastern part of the country Hungarian Kingdom from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, fleeing the pogroms associated with the Haidamak uprising in Ukraine and political instability as a result of the three sections of The Commonwealth and its final disappearance from the political map of Europe. On the other hand, during the reign of the Emperor Josef’s ІІ, who was a proponent of the Enlightenment, it was the Austrian Empire that implemented the Tolerant patent (1781), which removed many of the legal restrictions that Jews faced in other European countries.

The process of resettlement of Jews in Transcarpathia at the end of the XVIII-XIX centuries became almost explosive. When, for example, in Mukachevo in 1660, there was only one Jew, but in 1824, every third resident of Mukachevo was one. Subsequently, Mukachevo became almost completely Jewish city.

In 1700 in Uzhgorod there were only two Jewish families, and in 1724 there was already an entire Jewish community. In 1730, during the time of the chief ishpan of the Uzhan dominion, I. Druget, the issue of their citizenship was positively resolved. In 1860, Jews already made up almost 28% of citizens (with 30% of Ukrainians and 40% of Hungarians), had their own religious center, rabinat administration, the main synagogue with several branches, later a gymnasium, city and parish schools, a ritual bath, and a separate cemetery.

In all of Hungary from 1785 to 1870, the number of Jews increased 8 times. The rapid growth of their number is evidenced by the following data: if in 1869 statistics recorded 543,186 people, in 1880 – 624,738, in 1890 – 707,472, which was 4.77% of the total population. In one capital, the number of Jews then reached 122 thousand. It was not for nothing that the jokers of that time called it Yudapesht. The researchers attributed this to two reasons: natural, that is, large families, and intensive migration from neighboring Galicia.

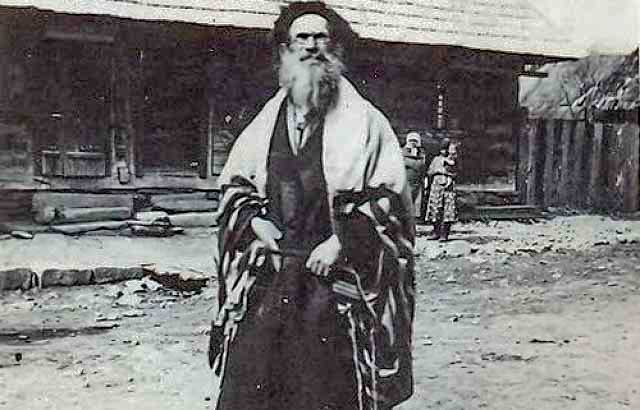

In General, the Jews who settled in Transcarpathia, as well as in other parts of Central and Eastern Europe, were Ashkenazi Jews who spoke Yiddish. The vast majority belonged to the ultraconservative religious trend Hasidism’s, its followers were devoted adepts of the so-called miracle-working Rebbe, and therefore Transcarpathia soon became a haven for strong Hasidic dynasties.

Historians and ethnologists have noted a number of specific features of Transcarpathian Jews: excessive loyalty to traditions and strong self-awareness. Here, for example, Zionism won much less influence among young people than in other regions. Transcarpathian Jews stubbornly refused to plunge into the irreligious twentieth century. In addition, Transcarpathian Jews very strictly adhered to endogamy. In the territory of the present Transcarpathian region before the Second World War, the proportion of mixed marriages was “a pitiful 0.9%”, while in strict communities of Slovakia – 5, and in Moravia – 30.

The Jews of Transcarpathia were the last medieval Jews in Europe. In contrast to the more cosmopolitan parts of the continent, they lived on a peculiar island of traditional lifestyle, more isolated from secularization influences than any other area of Jewish settlement in Eastern and Central Europe.

This closed world, incomprehensible to the outside eye, is perfectly reproduced in his book “Golet in the valley” by a famous Czech writer Ivan Olbracht (by the way, his father was a crossbred Jew, so he knew a lot of Jewish secrets). In fact, Olbracht created the same thing as Isaac Babel in his “Odessa stories” – the Jewish myth of Transcarpathia. But the Odessa situation was significantly different from the Transcarpathian one. The Jews in Carpathian in the XX century, they became mainly a working element. They worked not only in construction sites, sawmills, Handicrafts, small-scale agriculture, and horse-drawn transport, but also insmithies or even begging. However, the decline of the Jewish community in the 1920s and 1930s can already be clearly seen in Olbrachta.the wealthier moved closer to the capital or to richer countries. There were still beggars who found it harder to make ends meet every year.

However, the Jews managed to survive in the most difficult situations. They were able to do this primarily because they always helped each other. It is written in their sacred books that a tenth of their earnings should be given to charity. And they do this by helping poor tribesmen. And the amazing Jewish solidarity that helped them survive and not disappear among numerous peoples and faiths has long been a byword.

Transcarpathia in XIX – first half of XX century was known as “the land of shorerov” because of the large number of Jews who lived as “snorer”, that is vagrants, who collected alms in the neighboring lands. It can be argued that begging was acceptable and even considered a noble way to earn a living, but it caused hostility from other people who also did not have sufficient means to support themselves.

In General, Transcarpathia has traditionally been a territory with a low standard of living. Such poverty and misery remained a characteristic of the region for centuries. Areas such as the highlands and particularly the Committee Maramorosh they were known for their squalor, they were home to Jewish families with a large number of starving, ragged children who grew up in very difficult conditions. Their parents, representatives of the poor of mountain villages, lived in the same poor conditions as their Ukrainian neighbors. Residents of the forest areas could earn occasional hard physical labor, being employed as laborers, movers, and laborers. woodcutters’. In the more fertile lowland areas many Jews were engaged in agriculture: as land owners, they grew vegetables, wheat, and grapes, as well as raised livestock or worked as Milkmen. Among the Jews of Transcarpathia were farmers, some of them had small plots of land, where they grew vegetables and kept a small number of livestock and thus provided their food. Some did not have this, and they were forced to earn money by working for more affluent farmers – Jews or non-Jews. Some migrated to the Panonska plain for work while they were working in the fields, where they were usually paid with agricultural products that they used or sold themselves and so supported their families.

However, contrary to popular belief about Jews as merchants, only 25% of them were engaged in trade. On Verkhovyna, 90% of them earned money by transporting timber. The tavern was kept for 1.4% of the Jews. However, in General, merchants and other owners in 1908-1914 were divided in Transcarpathia by nationality as follows: Jews-48, Germans-29, Hungarians-21, Ukrainians-0.7.

The success in business of the Jews of Transcarpathia caused anti-Semitic sentiments among representatives of other nationalities of the region. However, anti-Jewish pogroms have never occurred in our region, as in other regions of Central and Eastern Europe. This was due to the fact that most of the Jewish population was as poor as the local Ukrainians, and worked just as hard physically to survive.

In the spring of 1944, almost all Transcarpathian Jews were loaded into freight cars and taken to Auschwitz-the world’s largest “death factory”. Of more than a hundred thousand Transcarpathian Jews, only a tenth survived. The rest remained forever in the Polish swamps. But those who returned home found ruined, lonely farmsteads that reminded of a recent family tragedy. It is not surprising that a significant part of Transcarpathian Jews who survived the concentration camp immediately after the war also emigrated to the West.

In 1959, more than 12 thousand Jews lived in Transcarpathia. Most of them came from the East with Russian and Eastern Ukrainians. It was a different world. If the Hasidim sought to differ as much as possible, carefully cherishing their God-chosen, then Soviet Jew on the contrary, they tried to disappear more loudly among the “goyim” (infidels). There was no language, no religion, no rituals. Nothing.

The system modeled ” a simple Soviet person – – Russified and marginalized. Many of these Jews were ashamed of their origin and hid it even from their own children. And along with this, the fascinating Jewish exoticism, so vividly described in the works, disappeared Of Olbracht.